What makes social media stories special?

Stories are nothing new – they’re how we process ourselves and the world around us. But we’ve never been telling more stories than today. And, it’s never been easier to hear the stories others have constructed. Stories “create identities for their tellers and audiences” [10], so as we create more stories than ever before, we’re exposed to more identities.

Stories as a format

The defining characteristics

Within the context of social media, the word “story” has come to refer to a very specific form of content. Stories combine a few distinct characteristics, creating a compelling formula:

- Stories have a vertical orientation, with an aspect ratio around 2:3

- Immersive full screen viewing and engagement.

- Stories play continuously – each post is on screen for only a brief period before moving to the following post.

- Ephemeral, since they’re preserved for 24 hours unless saved.

- Anchored to a time, place, and person, providing a close view of their reality.

Snapchat introduced the "story as a format" to social media in 2013, adding a more permanent posting option to an application that before had only allowed ephemeral, single-view messages.

The next significant point in story growth came in 2016, when Instagram introduced the feature to their platform. Since 2016, Facebook Messenger, WhatsApp, YouTube, and many other platforms have all added stories [5].

Breaking down the stories formula

Vertical orientation

The vertical orientation of stories matches how users hold their phones. With stories, users don’t need to turn their device to view videos. Plus, one hand can play, pause, and skip forward or backward. So, stories have a "lower friction" to engage with than traditional media on mobile.

The roughly 2:3 "inverted" aspect ratio also fits a historical preference for documents and content with a portrait orientation. This preferences dates back to at least Egyptian hieroglyphs [15].

They fill the screen

When viewed, social media stories are a full screen experience. No other applications or content are visible, minimizing distractions.

Continuous play

Continuous play means users must opt out of the experience after an initial engagement with a single story. Until a user exits the stories experience, they'll keep watching stories until they’ve seen every story from every account they follow.

This is like (but requires less active engagement than) the social media phenomena of an endless or infinite scroll. With infinite scroll, more content loads as a user progresses down a page, infinitely. It's a useful pattern when “each unit of content belongs at the same level of hierarchy and has similar chances of being interesting to users” [9]. TikTok presents an amalgamate of both the endless scroll and continuous play patterns.

Ephemeral

Social media stories are temporary by default. A stories user must decide to save a story or pin a story to their profile.

Stories are not the first ephemeral social media. Snapchat brought the idea of ephemeral social media content to the mainstream but initially focused on 1 to 1 or 1 to few distribution. Stories extend this form to a 1 to many relationship.

Anchored to a time, place, and person

Time: Several factors unite to create a pervasive sense of time and place within social media stories. A set "expiration date" means a story must take place at a time close to the present. Stories usually include a timestamp in the form of minutes or hours since posting. And stories posted most recently move to the beginning of the “story queue” on many platforms.

Place: Features like Snapchat’s “Snap Map” show stories posted nearby. Most platforms also include location-based filters or tags.

At the same time, stories exist in one shared place and time. They weave “co-present interactions and mediated distant exchanges into a single, seamless web” [1]. Story posters share context about their location. Viewers may see where their own location is relative to the location of the poster. And, they share information in a third, digital space [3].

Person: Story content often involves a camera anchored to a person. That camera may point towards the creator or the outside world. Ubiquitous cameras + stories = a portal into what someone else sees. As Nathan Jurgenson says, “social photos are not primarily about making media but more about sharing eyes” [8].

What are the benefits? What are the use cases?

Quick, fun content with added interactivity

Stories are a format with fewer (and different) norms than the rest of the social media network they're posted to. On a platform like Instagram, they may feel more casual or unfiltered than a standard post. Stories allow “a bit more fun amidst their regular posting of highly structured, edited, and perfected photos” [5]. And their temporary nature and personal feel let users more freely present a multidimensional self [4].

Empathy building

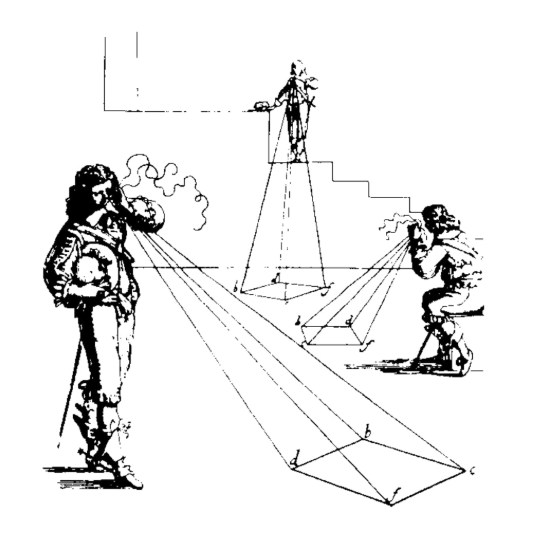

Before cameras existed, media portrayed the world as arranged for a human spectator. In Ways of Seeing, John Berger explains how the camera shifted the way we view the world. Rather than imagining “everything converging on the human eye” the camera forced a recognition that “what you saw was relative to your position in time and space” [2].

The focus of stories on place and time forces realization of the relative nature of self. An individual’s perspective might be different from one day to the next. And, many people may document the same event but focus on different things. Viewing social media as more self-centered than previous media ignores that it constantly exposes users to countless perspectives.

This constant exposure to different perspectives is certain to shift opinions. The people you interact with form and change your own personality. Stories present a more unfiltered and current view of those who post, deepening the interactions and connections between users. When you have a frequent, recent view into someone’s life, you’re more likely to accept them, their ideas, and their opinions.

Narrative benefits

Current attempts to describe the concept of narrative view it as something of a “fuzzy set” [12] roughly consisting of:

- Events, ordered within a temporal framework (Translation: events with a time attached)

- Connections between events, with causal connections having a higher level of narrativity than pure temporality (Translation: “first this happened, then because of that this happened” is more of a narrative than “first this happened, then this happened”)

- A focus on why things happened with “complication and resolution, or a clearly defined point of closure” [10]

Stories impart many of these benefits by default. Events are always documented within a temporal framework, and the format nudges users to document current events. On Instagram, for instance, uploading a photo or video from more than 24 hours ago automatically adds a date stamp. Snapchat applies a “from memories” for or “from camera roll” stamp to content that’s not posted at the time of capture.

The nudge to use stories to document the present pushes users to apply a narrative to their everyday life. And, if one raises a question with an initial post (“what’s going to happen?”) there’s an expectation that they will answer it with a follow up post, providing resolution.

What's the business case? What are the drawbacks?

From the platform perspective

As “the platform” (think Facebook & Instagram or Snapchat) social media stories make clear business sense. First, there’s a consumer demand for them. Look to the massive format growth rates experienced over the past few years for proof [5]. Beyond meeting a demand, stories bring in a wealth of data on user's habits and interests. Their immersive nature brings more deep engagement metrics.

And, the wide choice of engagements like voting, reactions, and filter use all create valuable data points. Platforms can use this data to improve experiences and attract new users. Or, they can use it to sell things to existing customers. They can use it ethically, or unethically. Probably, these platforms are doing a combination of all these things. Questionable? Yes. Lucrative from a business perspective? For sure.

For users + advertisers

Even with a simple business or creator account on Instagram - available to any user - viewable story metrics include [7]:

- Who viewed a story

- How many viewers tapped forward, backward, or exited

- Total impressions (did anyone view it multiple times?)

- How many viewers visited the poster’s profile

- How many users engaged with any content within the story

- Any votes or question answers a user submitted

That interaction data is great for influencers, public personalities, and marketers. Clicks, exits, and various forms of engagement like voting or responses can construct a sketch of an audience. Smart posters can use that sketch to test and optimize content. And, they can refine their sketch into a more full picture. Optimized content builds a strong brand and following.

Stories help inform advertising targeting. And, they give that targeted advertising a prime, trusted spot for users. Marketers can place their advertising between relevant organic content. And those ads autoplay and are a full screen, “opt out” experience.

Becoming a paid influencer can mean sponsored posts and deals to promote products. Perhaps more compelling are the secondary markets formed by users. For years, adult industry performers have sold subscriptions to private Snapchat stories. This isn’t a market sanctioned by Snapchat – the performers run a Snapchat account that for a fee, they’ll share the details of.

Recently, Instagram influencers have sold subscriptions to their “close friends” list. Instagram’s “close friends” feature lets users specify a few friends who will see a story or post. Enterprising users have figured out that they can charge followers to join the list. In return, followers might get exclusive posts or an inside view of someone’s life [14].

However, by sharing so much of ourselves, we may create a more narrow version of who we are. In turn, we’re forced to play that character. In “The Social Photo”, Nathan Jurgenson remarks, “in giving us too much self, the profile leaves us with less […] too much self is the self as a constraining spreadsheet” [8]. That freedom to share anything turns into an expectation to share a certain perspective, attitude, or sentiment.

That same freedom to share anything can feel like a compulsion to do so. A highly engaging format may also be highly addictive. The majority of US adults use social media, and most who use it log in on a daily basis [11]. Stories bring joy to users and provide a different outlet than many other forms of social media, but that doesn’t negate the negative consequences. It’s frightening how difficult these consequences are to assess, especially over a long time period.

Final thoughts + future directions

Stories represent an interesting evolution in social media formats. They serve as an amalgamate of many previous content forms, but layer new interactions on top. Bottom line: the “story as a format” space is still at an experimental stage.

These new experiences generate engagement, capture attention, and impact culture. Simultaneously, their recency and experimental status raise questions. Will the increased communication and empathy that stories - and more broadly, social media - bring to the table outweigh the possible harm?

How does one even begin to assess that harm? Innovations that generate more questions than answers may highlight a need to proceed with caution. The momentum of social media and social media stories may be hard to stop. But, we can ask questions, design thoughtfully, and monitor outcomes to make sure that inertia takes us in a good direction.

Works cited

- Arminen, I., & Weilenmann, A. (2009). Mobile presence and intimacy—Reshaping social actions in mobile contextual configuration. Journal of Pragmatics, 41(10), 1905-1923.

- Berger, J. (1977). Ways of Seeing. 1972. London: British Broadcasting Corporation and Penguin Books.

- Bhabha, Homi K. (2004). The Location of Culture. Routledge.

- Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. London: Harmondsworth.

- Harper, K. (2019, February 21). Social Media Stories Should Be the Focus of Every Digital Storytelling Strategy. Here's Why. Retrieved from https://www.skyword.com/contentstandard/social-media-stories-should-be-the-focus-of-every-digital-storytelling-strategy-heres-why/

- Hine, C. (2000). Virtual ethnography. Sage.

- Instagram (2019). Guide to Get Started on Instagram for Businesses. Retrieved from https://business.instagram.com/getting-started

- Jurgenson, N. (2019). The social photo: on photography and social media. London ; New York: Verso Books.

- Loranger, H. (2014). Infinite Scrolling Is Not for Every Website. Nielsen Norman Group, Evidence-Based User Experience Research, Training and Consulting. Retrieved from http://www.nngroup.com/articles/infinite-scrolling

- Page, R. (2013). Stories and social media: Identities and interaction. Routledge.

- Perrin, A., & Anderson, M. (2019). Share of US adults using social media, including Facebook, is mostly unchanged since 2018. Pew Res. Cent. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/04/10/share-of-u-s-adults-using-social-media-including-facebook-is-mostly-unchanged-since-2018/

- Ryan, M. L. (2007). Toward a definition of narrative. The Cambridge companion to narrative, 22-35.

- Smiley, Melinda (2019). Tinder Debuts Swipe Night, Its Apocalyptic Choose-Your-Own-Adventure Series. Adweek. Retrieved from https://www.adweek.com/creativity/tinder-debuts-swipe-night-its-apocalyptic-choose-your-own-adventure-series/

- Tiffany, K. (2019, September 17). 'Close Friends,' for a Monthly Fee. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2019/09/close-friends-instagram-subscription-charge-influencers/598171/

- Wearden, S. (1998). Landscape vs. portrait formats: Assessing consumer preferences. Future of Print Media, 1-10.